Buckle Up or Else: Texas Supreme Court Holds Plaintiffs Responsible for Failure to Wear Seat Belts

By Tasha L. Barnes • Dec 16, 2015

By: William R. Scott, Ph.D., Biodynamic Research Corporation, Tasha L. Barnes, Thompson Coe, Michael L. Copes, Biodynamic Research Corporation

Published on 7/25/16 by The Review of Litigation.

On February 13, 2015 the Supreme Court of Texas issued a ruling in Nabors Well Services, Ltd. v. Romero, 456 S.W.3d 553 (Tex. 2015) which changed the rules in Texas regarding the admissibility of the use or non-use of a seatbelt by a plaintiff that was injured in a car crash. This ruling provides a new way for defense attorneys to help their clients. Many Texas defense attorneys may not know the methodology behind preparing a seatbelt defense in a case where a plaintiff was injured in a car crash because it has been so long since the seatbelt defense was allowed. In some cases it’s even possible an attorney representing the plaintiff may want to present a seatbelt case to prove the negative; i.e., the non-use of a seatbelt did not affect the injury outcome of the plaintiff. The purpose of this article is to discuss some of the nuances of this ruling and provide an overview of the methodology behind a seatbelt defense.

By way of background, in deciding Nabors Well Services, the Supreme Court of Texas overturned its precedent regarding seatbelt use that was created in its 40 year old decision in Carnation Co. v. Wong, 516 S.W.2d 116 (Tex. 1974). This prior ruling was based on the reasoning that a plaintiff’s failure to use a seatbelt may exacerbate their injuries; but their failure to use a seatbelt did not cause the car crash, and therefore the failure to use a seatbelt should not affect a plaintiff’s recovery. Between 1974 and 1995, Texas operated under an all-or-nothing rule in negligence cases. If the plaintiff was found to have any amount of negligence the plaintiff could not recover any damages. Subsequent to 1995, a plaintiff’s negligence could be apportioned alongside a defendant’s without entirely barring the plaintiff from any recovery. As long as the plaintiff’s own responsibility did not exceed 50% the plaintiff was entitled to a recovery reduced by their percentage of responsibility (Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code §§ 33.001, 33.012). In Nabors Well Services, however, the Supreme Court of Texas stated that the legal environment and societal views on safety have changed since 1974. Unlike 1974, seatbelt use is now required by law and seatbelts are used by the majority of drivers and passengers in Texas. In 1974 lap and shoulder belts were new in the front seats of passenger cars and the national occupant use rate was very low, less than 10% (1). As of 2012 the occupant use rate had climbed to 93.8% in Texas (2). The Court held, the “relevant evidence of use or nonuse of seat belts, and relevant evidence of a plaintiff’s pre-occurrence, injury-causing conduct generally, is admissible for the purpose of apportioning responsibility….” Following Nabors Well Services, a jury may now consider whether plaintiff’s failure to use a seat belt, although it did not cause the crash, may have played a role in causing the plaintiff’s injuries.

It is important to note, the holding in Nabors Well Services also directly addresses the responsibility of the adult driver to properly restrain children. Therefore, when an infant or child is injured in a crash juries may now consider whether the responsible adult was negligent in properly restraining the minor under the applicable statute, Tex. Transp. Code §§ 545.412 & 545.413.

Significantly, the Naborsopinion represents a dramatic shift in the application of the proportionate responsibility statute to include injury-causing evidence against a plaintiff. The Court through a thoughtful, lengthy analysis clearly defined the probative value of seatbelt evidence and provided a practical guide as to how the evidence will be admitted and submitted to the fact-finder. After careful analysis of the distinction between occurrence-causing and injury-causing conduct, the Court found “the conclusion is unavoidable that failure to use a seat belt is one way in which a plaintiff can ‘cause or contribute to cause in any way’ his own ‘personal injuries’ or ‘death.’” Nabors, 456 S.W.3d at 562-563. The proportionate-responsibility statute calls for an apportionment of fault for “personal injuries” and “death” rather than for the underlying occurrence that introduced a sequence of events in which the end result is potentially influenced by whether the plaintiff acted unreasonably or even broke the law. Based upon the plain-language of the statute, the Legislature both intended and required fact-finders to consider relevant evidence of a plaintiff’s pre-occurrence, injury-causing conduct. Id.at 563. The Court’s conclusion directly contradicted and specifically overruled prior precedent holding that a plaintiff’s injury-causing negligence cannot reduce a plaintiff’s recovery. Thus, the Court’s decision to allow admission of this type of evidence for determination of proportionate responsibility was a substantial change in the concept of contributory negligence.

The Court noted that the relevance of this type of evidence will still be within the province of the trial court and that it will only be relevant if a defendant can establish that nonuse caused or contributed to cause the plaintiff’s injuries. Notably, the trial court should first consider the evidence for the purpose of making a relevance determination outside the presence of the jury. Id.For this reason, it will be extremely important for litigants on both sides of the case to have reliable, competent expert testimony which will survive a Robinsonchallenge proving the causal connection or the lack thereof.

Additionally, the Court provided practical guidance as to how to construct a jury charge when seat belt evidence is to be considered. With respect to this issue, the plaintiff’s negligence should be submitted if he or she was in violation of the Texas seat belt law. If the plaintiff is a minor child, the jury may apportion responsibility to the person upon whom the law places the burden to properly restrain the child. Id.at 563-564. The court emphasized the need to not deviate from a single apportionment question. A jury can consider a plaintiff’s pre-occurrence, injury-causing conduct alongside his and other persons’ occurrence-causing conduct. “There is nothing about injury-causing conduct that renders it incompatible with being considered alongside occurrence-causing conduct in one responsibility apportionment for the harm suffered by the plaintiff.” Id.at 564.

The Court also clarified that the failure to use a seat belt is not a failure to mitigate. A failure to mitigate occurs post-occurrence and not pre-occurrence such as the nonuse of a seatbelt. A plaintiff’s post-occurrence failure to mitigate his damages operates as a reduction of his damages award and is not considered in the responsibility apportionment. It is only the plaintiff’s pre-occurrence, injury-causing conduct that should be considered in the responsibility apportionment. Id.

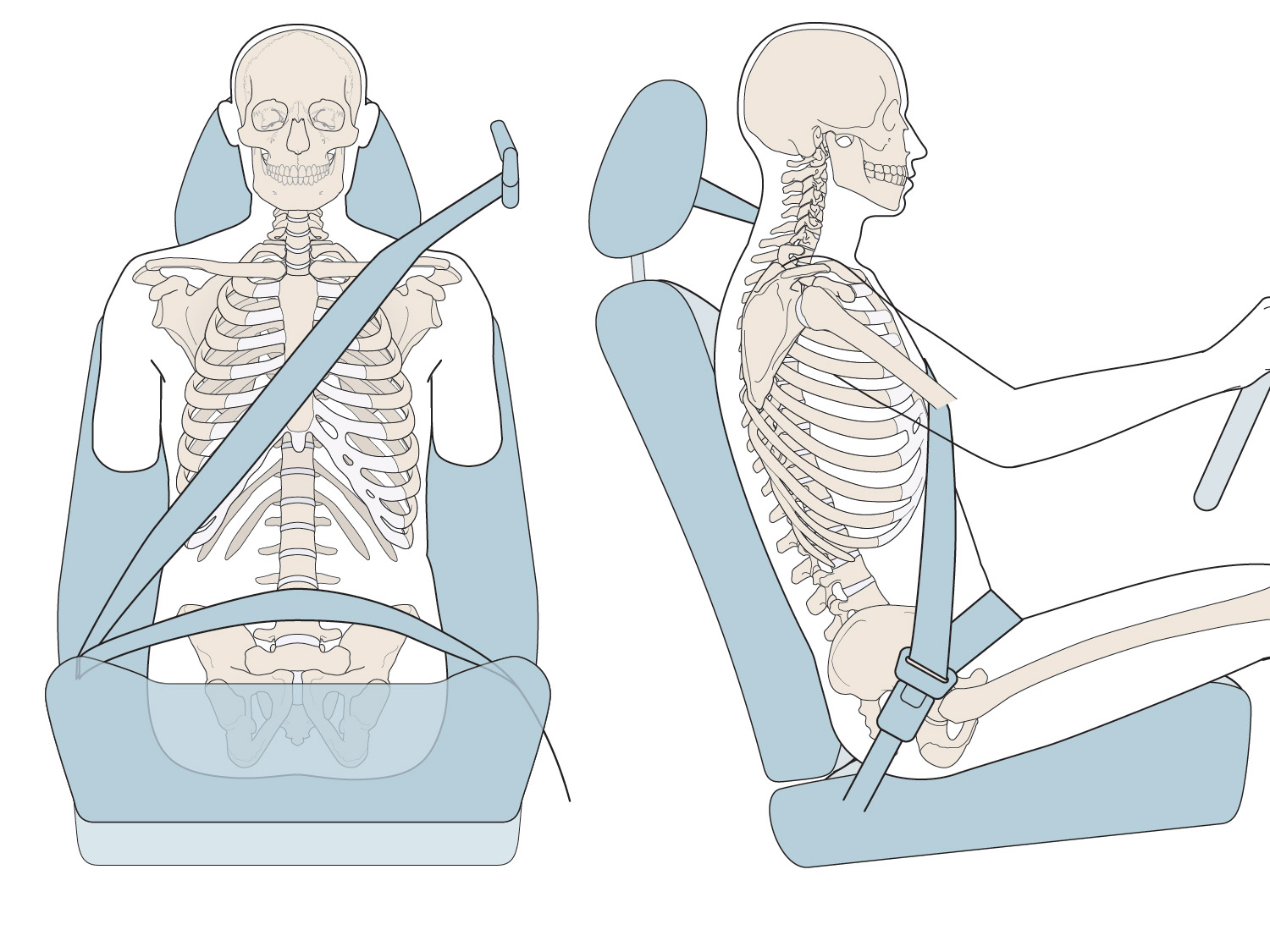

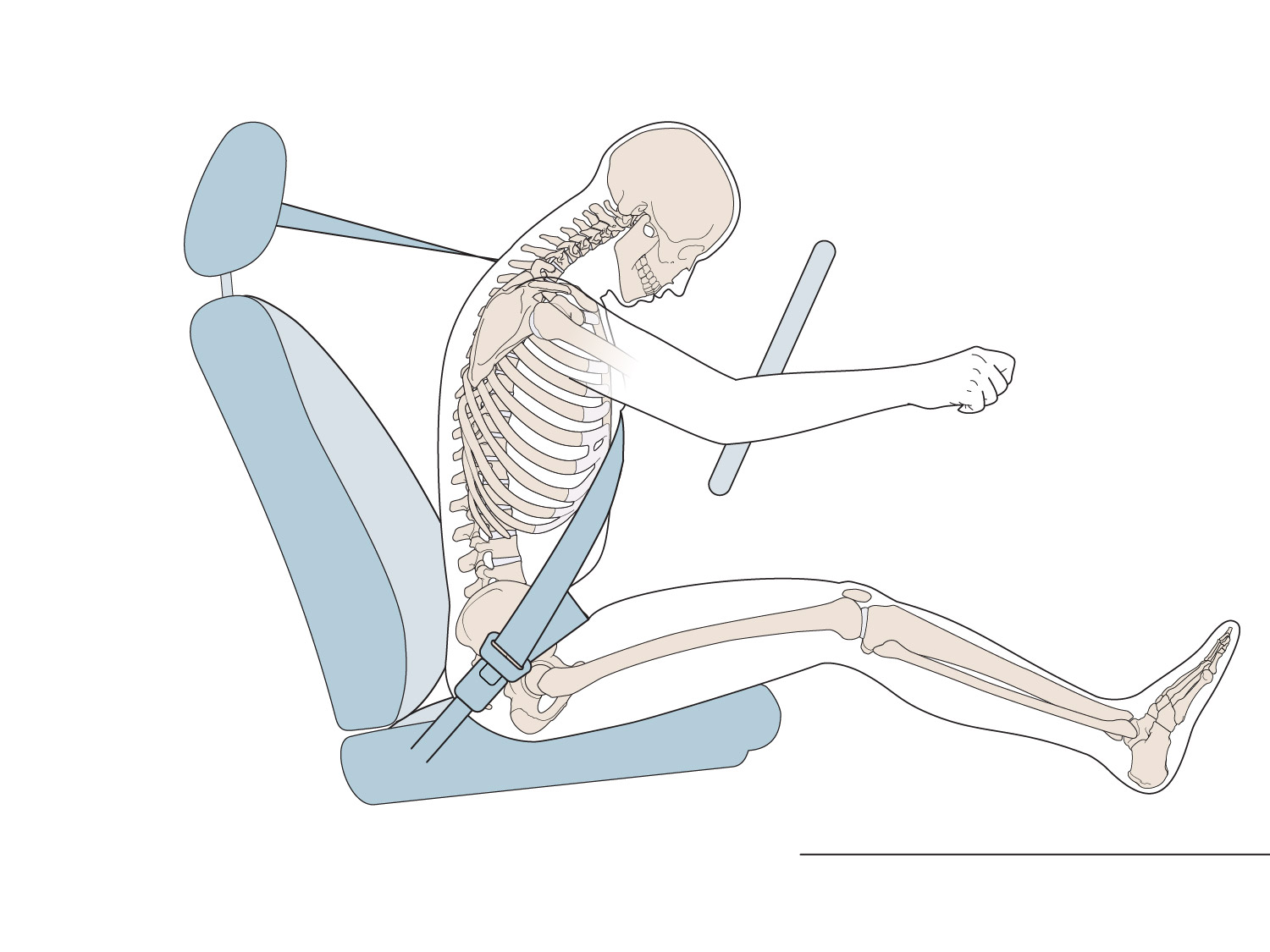

Crash field data collected over the last 35 years makes it very clear that wearing a seatbelt properly can significantly reduce injury risk and death in all types of crashes (3,4). In some crashes the proper use/non-use of a seatbelt is the difference between a few bruises and a fatal injury. When used properly the seatbelt will apply restraining forces to strong boney structures, which in turn will make the occupant’s body follow the new post-crash motion of the vehicle. Exhibit 1 shows a properly worn 3-point seatbelt on a person with the underlying boney structures visible. In a frontal crash, shown in Exhibit 2, the occupant would move forward relative to the vehicle interior and the shoulder belt would interact with the left clavicle, rib cage and sternum and the lap belt would interact with the pelvis. A properly worn seatbelt would apply a restraining force to these strong boney structures and they would in turn slow down the organs in the thorax and the abdomen through their anatomical attachments. The seatbelt also provides protection to the occupant in crash types other than frontals; such as rear, side and oblique impacts, and rollovers and crashes composed of multiple events.

Exhibit 1. Illustrations that show the position of the bones of the thorax and the abdomen relative to the lap and shoulder belt parts of the seatbelt.

Exhibit 2. In a frontal crash the occupants move forward with respect to the vehicle interior and the shoulder belt applies a restraining force to the clavicle, sternum and rib cage and the lap belt applies a restraining force to the pelvis.

But what if the seatbelt is not worn properly? How is this situation handled in light of the ruling in Nabors Well Services? Our experience tells us that when occupants wear their seatbelt improperly these occupants may have unusual injury patterns in a crash and usually these occupants are coded in the police crash report as having worn their seatbelt. The first responders may remember removing a restraint system from the occupant but their focus at the crash scene is on helping the injured occupant, not observing how the restraint system is worn. However, the resulting unusual injury pattern will be a flag for an experienced attorney or a trained biomechanical expert that even though the seatbelt was worn, it was not worn properly. Nabors Well Services does not directly discuss improper use of seatbelts, although the ruling does focus on what a plaintiff may have done to cause their injuries, in this case not wearing their seatbelt properly. It follows then that the intent of the ruling, although not the letter, is to hold people accountable for their actions in causing their own injuries, and an improperly worn seatbelt should be treated as an action that led to an injury, or the same as not wearing a seatbelt at all. Therefore, a seatbelt defense should apply to cases where improperly restrained and unrestrained minors, improperly restrained occupants, and unrestrained occupants were injured in a vehicle crash. Now we move on to actually developing the seatbelt defense.

There are three steps an attorney needs to follow in order to develop a seat belt defense: 1) cost benefit analysis of employing the seatbelt defense, 2) analysis by an expert of available evidence to determine how an occupant was injured and whether an occupant was using, improperly using, or not using a seatbelt, and 3) if the expert’s opinion is that the individual was not restrained or improperly restrained, determining what level of injury would have occurred had the occupant been properly restrained.

The first step in developing a seat belt defense is the initial decision of whether a seatbelt defense may assist an attorney in the defense of a case. It is axiomatic to say it is pointless to spend time and money on an analysis that would eventually provide no benefit. The decision on whether to go forward is, however, somewhat subjective. An experienced personal injury attorney should be able to make an educated decision based on the information that is available and based on their experiences with analogous defenses. An inexperienced attorney may want to have an expert assist in evaluating the available information to help make this initial decision on whether to employ this new strategy. If the decision is made to proceed with a seatbelt defense the second step is to determine what did happen in the crash to cause the plaintiff’s injuries.

Initially there may be a suspicion that the plaintiff was not wearing their seatbelt or not wearing it properly and the second step in the seatbelt defense involves confirming or denying this hypothesis by analyzing the available evidence. Detailed information about the crash is required to start the analysis and an attorney needs to make sure that the proper information is available to his experts, including the Texas Peace Officer’s Crash Report, witness statements, and the acute phase medical records. Of particular importance in the medical record are the EMT reports and the acute phase radiological studies. The EMTs are the first medical personnel on the scene and their report may provide the earliest information on how the plaintiff was restrained, if at all. The acute phase radiological studies provide information on where external forces were applied to the body, including the forces applied by a seatbelt. These radiological studies can provide information on whether a seatbelt was worn and whether it was worn properly. Specific vehicle information needs to be available to your expert in the form of on-scene photographs or post-crash photographs taken after the vehicle has been removed from the scene. The ideal situation is an inspection of a well preserved vehicle by the expert where the external damage and any occupant witness marks can be documented as well as the state of the seatbelt systems. An inspection of the seatbelt systems can provide valuable information on the use or non-use of the seatbelts by an occupant in a crash (5,6).

The type of accident that the vehicle and its occupants were involved in will dictate the type and magnitude of the biomechanical forces that an occupant had applied to their body in a crash and the level of complexity in analyzing what happened in the actual crash. A crash with complex vehicle motions and multiple events may require an expert in accident reconstruction to help explain and quantify the vehicle dynamics in the crash. Conversely, in a simple planar crash, a download of the airbag’s control module may be sufficient to quantify the vehicle’s accelerations and the change in velocity experienced by the vehicle. A biomechanical expert will then use the vehicle dynamics to determine how the plaintiff moved inside the vehicle, how the plaintiff interacted with the seatbelt or other parts of the vehicle, and how these interactions created the forces that led to the injuries. After evaluating the available evidence, an expert can render their opinion regarding whether a particular occupant was using, improperly using, or not using their seatbelt system. If the conclusion in the second step is that that the plaintiff was not wearing the seatbelt or was wearing it improperly and this most likely caused the plaintiff’s injuries, then the next step in the analysis is to determine the injuries that would have occurred had the plaintiff worn their seatbelt or worn it properly.

The third step in the seatbelt defense analysis must quantify the reduction in injury risk if a plaintiff had worn their seatbelt properly. In many cases this last step is very simple. For example, in a rollover crash where a plaintiff was fully ejected from the vehicle and seriously injured it may be easy to show that had that plaintiff worn their seatbelt and remained in the vehicle they would have received only minor injuries. In other cases it may be much more difficult and require a detailed analysis. Since this third step will involve risk analysis it may be heavy on the theoretical side. Another approach is to do testing to help quantify the differences between the risk of injury for a properly belted and unbelted or improperly belted plaintiff. The ultimate expression of case specific testing would be to run two crash tests; one with a test dummy properly restrained and one where the dummy is not restrained. Whatever approach is used to show a reduction in injury risk it must be explainable, i.e., you must be able to get in front of a jury and have your expert be able to explain the concepts in a manner that the jury can understand.

So what does this mean for savvy practitioners involved in automobile litigation? From a plaintiff’s perspective, developing evidence that seatbelt evidence is not relevant to the plaintiff’s injuries and properly presenting it pre-trial could avoid the issue altogether. Barring that, offering evidence to the jury that the plaintiff’s failure to wear his seatbelt did not cause or exacerbate any injuries could be essential to any recovery. For the defense, evidence that a plaintiff’s own negligence in failing to wear his seat belt caused his own injuries results in a complete bar to recovery, even in a case in which the defendant’s negligence clearly caused the accident. For these reasons, an initial assessment of the use or non-use of seatbelts is essential in any automobile injury litigation.

This article was intended to provide an overview of the new status of the law in Texas following the Nabors Well Services ruling regarding the admissibility of seatbelt use in cases where a plaintiff is claiming to have been injured as a result of a car crash. A three step process to develop a seatbelt defense was described. The first step is an initial analysis of whether use or non-use of a seatbelt is at issue, and the second step is the analysis to determine how the plaintiff was injured and as part of that, how they were utilizing their seatbelt at the time of the crash. If this second step determines that the plaintiff was not using their seatbelt or not using it properly, then the third step of the analysis looks at the injury risk had the plaintiff worn their seatbelt properly.

References

1. Traffic Safety Facts 2013: A compilation of motor vehicle crash data from the fatality analysis reporting system and the general estimates system. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. DOT HS 812 139. 2015 Jun.

2. Occupant protection. Traffic Safety Facts – 2010 Data. DOT HS 811 619. 2012 May:7.

3. Evans L. How we know safety belts reduce injury and fatality risks. Issues in Automotive Safety Technology. Offset Frontal Crashes, Airbags, and Belt Restraint Effectiveness (SP-1072). SAE #950241. 1995:7-10.

4. Cummings P; Wells JD, and Rivara FP. Estimating seat belt effectiveness using matched-pair cohort methods. Accid Anal Prev. 2003; 32(1):143-9.

5. Bready JE; Nordhagen RP; Kent RW, and Jakstis MW. Characteristics of seat belt restraint system markings. Accident Reconstruction: Analysis, Simulation, and Visualization(SP-1491). SAE #2000-01-1317. 2000:517-526.

6. Raymond DE; Bir CA; Begeman PC; Chien H-C, and Wheeler JB. Forensic determination of seat belt usage in automotive collisions: Development of a diagnostic tool. Accident Reconstruction (SP-1999). SAE #2006-01-1128. 2006:125-138.